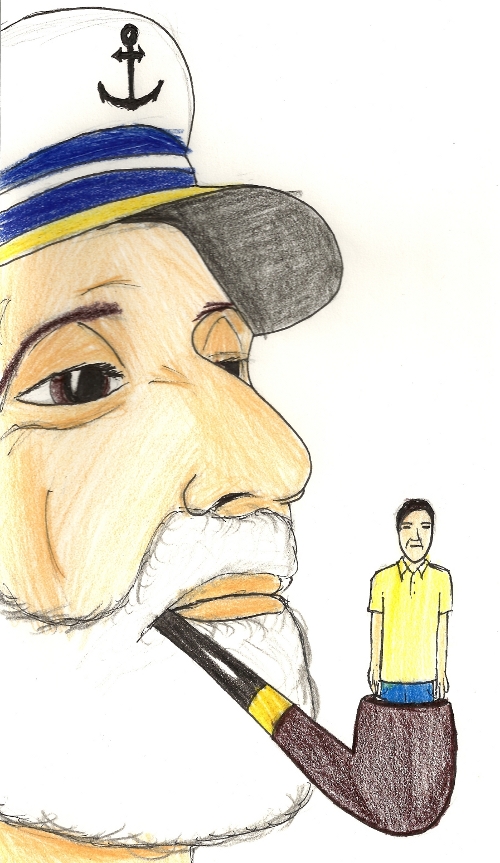

The Difference Between My Girlfriend and a Sea Captain

MUSIC BY JOSEPH SACHS

ART BY PATRICK COYLE

I first saw her hunched over the bar at McLoughlin's one evening in November, the sleeve of her sweater rolled up past the elbow, displaying to Eddie the bartender a ghastly burn that covered most of her inner forearm.

"I'm serious, Eddie, you motherfucker," she demanded. Her accent was Irish. "Put down the goddamn glass and feast your eyes on this."

I was alarmed that anyone was speaking to Eddie this way -- Eddie, the most angelic bartender in all of Queens County.

"It's a pretty bad burn," Eddie said, glancing quickly at her arm and then away. The skin there was purple and scabbed, infected-looking, layers of it clearly dead.

"You ought to get your fucking medical license, Eddie," the woman said. She sounded genuinely angry. The other men at the bar were silent, watching her out of the corners of their eyes. We were all, I think, a little afraid.

I stared at her profile. She looked like no woman I'd seen before. All the girls I knew seemed like twigs and this girl -- this woman -- was a redwood. She had an explosion of red hair over which she'd pulled a dark wool cap. No curves were discernible under her thick blue sweater or her jeans, too big for her, which she had belted with a line of fraying rope.

"Would you like to know how I got it?" she asked Eddie, her arm still extended.

"How?" He sounded nervous.

"This past summer I was frying burgers in Virginia," she said. "And one night shift I'm there alone, a couple of patties on the fryer for this lady and her kids, when this big beastly fucker sits down at the counter. And he's a hairy son of a bitch, mean-looking, skin like rare steak, you know? And he says to me, \'You a dyke or something?' Now, I'm used to that shite; I barely blink. But there are kids nearby, you know? And so I say, \'Is this all about how small your dick is, sir? Is that what's really upsetting you?' And he's drunk, right? So. He leaps over the counter and knocks into me and my arm slams down onto the fryer and it sizzles, is the fucking thing. And now I'm pissed off, screaming. So he starts to stumble away, but I grab his legs and he falls–BAM!–onto the linoleum and then I get on him and hold my arm up to his face and I say, \'See this? See what you fucking did?' and it's bleeding and he's crying and trying to push me off but he's too drunk and he's crying too fucking hard." She took a breath and a sip from the short glass in front of her. "He got six months for that and I got the hell out of Virginia."

It only took me a moment of listening to appreciate that she had the most gorgeous voice I'd ever heard -- heavy and low and expressive, the Irish a lilt that made every "fuck" a sudden jangling burst of music. As she spoke I moved towards her, slid silently onto the stool by her side. When her story was done, she grinned at Eddie and I saw that one of her bottom front teeth was missing. The shock of black space ran through me like a cutlass.

"That was an incredible story," I said.

She turned and took in my smile, my pale yellow polo shirt, my youthful haircut.

"Oi!" she exclaimed. "If it isn't Christopher fucking Robin!"

***

For the rest of the night, she let me sit beside her. She seemed to relish the attention. She called me a pussy when I asked if I could buy her a beer. She drank apricot brandy, no ice. Each time Eddie refilled her drink she took out a small silver flask of something clear and poured a swig into her glass. Her violet eyes seemed perpetually on the precipice of a wink. Looking into them I always felt I'd just missed one. How I cursed myself for missing those winks!

She had a host of other gruesome wounds, which she was only too delighted to display, and I absorbed the sight of every jagged white scar, the strange misshapen bridge of her nose from the three times it had been broken, full chunks of flesh which at one time or another had been separated forever from her substantial gut. I wanted to put my fingertips in the empty spaces they left behind.

Her first name was Mary.

Long after midnight, she stood and produced from her pockets two handfuls of quarters, which she dropped onto the bar. She called Eddie over with a whistle and he slid the coins into the cup he'd made of his hand–happy, I suspect, to see her go.

"You're leaving?" I asked. "Already?"

Mary licked her lips. "Isn't it a school night?"

"I'm out of school," I stammered, embarrassed that she took me for younger than my twenty-five years. She laughed and, without saying goodbye, hobbled to the door; she had a pronounced limp that made me imagine immediately a peg leg inside her black rubber boots. "Wait up!" I called, but if she heard, she took no shame in blithely ignoring me.

I had no cash and had to wait for Eddie's machine to read the magnetic strip of my debit card, all the while dodging the suspicious look he gave me. I'd been a regular since I'd moved to Queens in August, forsaking the trendy Manhattan happy hours to which my co-workers at the investment bank were forever inviting me in order to sit alone in this poorly-lit space and eavesdrop on the other patrons–men so weathered, they looked as if they'd come from a shift at a coal mine.

Eddie liked me. He liked that I sometimes came in with a briefcase. When the newscasters on the TV said "recession," Eddie asked what it meant, then watched my mouth move as I explained. He'd never seen me interact with another customer, and now I felt he was moving purposefully slowly, as if to widen the physical distance between Mary and me. Finally I scribbled my name on my receipt and burst onto the sidewalk. She'd only progressed a block and a half east. I ran to catch up but once I was beside her, she made no acknowledgment of my presence until, five blocks later, she stopped in front of a Greek restaurant.

"This is where I get off, Christopher Robin," she said, turning to me.

"Would you like to get dinner with me sometime?" I asked.

Mary squinted her left eye and looked at me shrewdly with her right. "If you're here to see my papers, just tell me you want to see my goddamn papers."

"No!" I said. "I like you, Mary. I just want to know more about you."

"I'm not a bloody zoo animal," she grumbled.

"Of course not!"

We stood there for a full minute, maybe longer, while she sized me up with a scowl. I gazed into the large glass windows of the restaurant and saw a man and woman at a table looking back at me, laughing. Then suddenly Mary had her hands around my hands. Her skin was callused and hot. She pressed her thumbs into my palms so hard that her arms shook, and by extension, mine shook as well.

"These are hands that have never seen a day's work," she snorted. "These are city hands. These are Harvard hands."

"I went to SUNY New Paltz," I said.

Mary let go, and after a moment, she spit on the sidewalk. She took a large ring of keys off a belt loop and unlocked the door next to the restaurant's entrance. Then she turned to me with the door held open, as if waiting for me to pass through. "Alright," she said.

"Alright?" I echoed.

"Alfuckingright," she snapped. "But so help me Jesus if you try to hold me I will not hesitate to put a knife in you. Do you hear me?"

I nodded and entered the cramped stairwell. Passing Mary I breathed in her peculiar scent–sour and wet, like a piece of seaweed on a rock. She shoved me aside and began to climb the two flights to her apartment. More than once it seemed she was about to lose her footing, and I put out my hands to support her. But she never quite stumbled, and each time I pulled back quickly, wondering how seriously I was meant to take her threat. A thought flashed in my mind -- how mysterious this woman was, how magical -- and left just as quickly. I had a curious sensation in my stomach, like I was setting off on some necessary voyage, one I'd been led closer and closer towards with each step I'd ever taken.

The apartment was sparse. There was a kitchen on the left -- unwashed dishes on every surface -- and a living room furnished solely with a couch. A few crude paintings of boats hung on the walls, unframed; from the tears in the canvas, I guessed they'd been picked up on street corners. I assumed the closed door on the right was Mary's bedroom. Beyond that a cluster of fishing poles leaned against the wall. I glanced up and saw the thin skeletons of assorted fish, hung by transparent thread from the ceiling like demented wind chimes.

I turned to Mary, burning with questions and with desire. She unceremoniously unbuckled my belt and pointed to the couch.

"There," she said.

She kept her boots on. When I tried to kiss her she put her hand on the top of my head and pressed me down onto her chest, into the stale wool of her sweater. She was strong. I pushed, tried to lift my head, look at her, but she pushed harder. Eventually I gave up. When it was over I sat beside her on the couch and gazed at the freckles that covered her thighs.

"Mary," I said, "Mary–"

But she pulled her jeans back up her legs, fished her flask from her pocket with one hand, and held up the other to silence me. "Please," she snapped. "Spare me."

***

From that moment on, we were inseparable. Or rather, Mary went where she pleased and I found it physically impossible to do anything but follow. I abandoned the life I led before I met her. I never went back to my own apartment. I quit my job and took up dishwashing at McLoughlin's to be close to her. In a letter to my mother I said I'd gotten a job teaching scuba lessons in Australia. It was the first thing I thought of. Don't try to reach me, I wrote, you won't have any luck. I threw away my cell phone. I fell off the grid. I tried to grow a beard. All I managed were patches that grew on my cheeks and my neck in imperfect squares.

But it was worth it, oh, how it was worth it to be close to her -- or at least as close as she would allow. To hear her raspy, wet, tubercular laugh at my pitiful beard. To accompany her to every meal at McLoughlin's; to wash her dishes when she was done. She liked heavy foods–boiled potatoes dipped in cream cheese, sausages and fried onions. She'd rant about steak and kidney pie while Eddie winced. "I'll bring a lamb in here myself and cut it open," she'd cry, banging her fork like a gavel, "but if I don't eat a decent steak and kidney pie sometime soon, I'm going to blow my fucking brains out." She drank what Eddie poured and when she ran out of quarters she switched to her flask, but besides always seeming a little hazy-eyed, a little unsteady, and extremely belligerent, she never seemed drunk.

When I finished a shift I'd walk up and put a hand on her back, which she'd shrug off. "Christopher Robin needs attention again?" she'd say loudly. "Christopher Robin's not getting his cock sucked enough in the Hundred-Acre Wood?" But back in her apartment she treated me with an indifference that seemed to border sometimes on tenderness. She'd lie on the couch with her boots in my lap and play "Hard Times Come Again No More" on an accordion, singing raggedly along. She taught me how to smoke a pipe and we'd walk around in the early afternoons with a perpetual cloud of sweet-smelling smoke above us. On the rare night she did not eat at McLoughlin's, she'd cook for us both, fish–smoked sturgeon, red snapper, Scottish salmon–that she'd bought wrapped in white paper from the fish market on Broadway. When we finished she'd boil the bones clean and add them to her collection on the ceiling.

All the while I asked her the requisite questions about her past -- where did you come from and why are you here and who have you loved and what makes you happy -- which she never answered sufficiently.

"What's your favorite Christmas memory?" I asked her Christmas morning, as we sat on the living room floor, sharing a plate of bacon.

"Are you fucking kidding me?" she responded.

I'd gotten her a silver necklace with a charm in the shape of an anchor, which she'd smiled wryly at and placed in her pocket. She'd gotten me nothing.

I tried to not to take it personally. I suspected her resistance to my love was a cover for some deep and lasting hurt. I wanted to get inside her, to touch her internal scars the way I stroked the external ones when I could be sure she was asleep. I wanted to tell Mary about my own pain. But my stories lacked the urgency I figured would attract her -- they were all about bones I'd watched other boys break, camping trips I'd taken with my parents -- so I began to lie. She listened without apparent interest as I recalled fabricated fistfights, made-up women whose hearts I'd broken in despicable, implausible ways. Sometimes I felt I was breaking through. Most nights I stayed on the couch and she slept alone on the twin-size mattress which lay on her bedroom floor. But on cold nights, she began to call out to me, her voice a strangled mewing which I never heard otherwise. We'd lie on our backs, shoulder to shoulder, as she was adamant that my hands never rest uselessly upon her. It was when I awoke those mornings, the windows filled with sun, my breathing light so as not to remind her of my presence, that I was at my happiest, my most carefree in love.

Other days were harder. Once I walked into the living room to find her wiping a grimy-looking rag across one of the fishing poles. I was overcome with longing.

"Will you take me fishing with you one day, darling?" I asked, forgetting for a moment her strict edict against terms of endearment. Mary spat -- onto her own carpet! -- and looked at me with utter loathing.

"I don't sail," she snarled, "and if I did, you can be well fucking sure that I wouldn't want some noodle-armed American knobjockey tagging along, mucking everything up."

I didn't broach the topic again. And I began to start each shift at McLoughlin's with ten push-ups in the back kitchen. But I began, I admit, to grow a little frustrated. This was my girlfriend, this was my girlfriend, I said to myself, even though she would have objected to the word, possibly with violence.

I'd spent every moment with her for months, but I was no closer to knowing her than I'd been the night I stood beside her at the bar and gazed at the revolting burn on her forearm. Mary had a past that she alluded to in general terms -- a past full of knife fights and large blank spaces where memories ought to have been. But I knew there was something tragic about her, besides her inability to get through the day without a drink. Standing at the sink in McLoughlin's one afternoon, pulling soapy dishes out of the scalding water, I began to wonder about her unspoken affinity for the ocean -- the fishing poles she never used, the paintings on her walls, the fact that she dressed as if she were expecting to step onto a barge at any moment. I imagined richly detailed disasters that might have befallen her over the anywhere between twenty-nine and forty-eight years she'd spent on this earth. Drowned siblings, shark attacks, icebergs, unexpected gales -- anything that could shut a woman down, make her hard. I peeled off my rubber gloves and walked out into the empty bar, where Eddie was filling out the crossword in the free paper people shoved into your hands on the subway. Mary, to my knowledge, was still asleep at home.

"Eddie," I said. "Can you think of any story Mary's told about fishing?"

Eddie glanced up at me, his expression a little wary. He scratched the back of his neck with his pen. "Can't say that I do," he said, and he returned his attention to his puzzle.

"Me neither," I said. I sat across the bar from him. "But it's a little odd, wouldn't you say? Doesn't she seem preoccupied with the sea? The way she talks, and her peg leg…"

"Peg leg?" Eddie said, looking alarmed. "Is that why she limps?"

I had never confirmed that her leg was prosthetic. She still never took her boots off when we were intimate. "Yes, of course," I said, "but she doesn't like to talk about it."

"Well," said Eddie. He shrugged. "I guess she does have that sort of quality about her. But you'd know better than me."

"But I don't," I said. Eddie pulled a clean glass from under the bar and set it on the table in front of me. He selected a bottle of whiskey and poured just a taste of it into the glass. I gulped it down and my throat burned.

"Listen," said Eddie softly. "When you first started coming in here, I could see you were a kid with a real bright future. You're smart. Too smart to be washing dishes all your life. Before you met her, you used to wear suits. You used to get haircuts."

I glanced at my reflection in the wall-length mirror over Eddie's shoulder. I did look shabby, my hair well past my ears, my beard still sparse. I saw, too, the darkness beneath my own eyes, which gave my face a haunted appearance. I seemed -- I was suddenly proud to notice -- tough. Like someone who'd seen trauma and come out with stories to tell.

"I think I look okay," I told him.

"I'm just saying," Eddie sighed, "I don't know what you think you're gonna get out of this relationship. The guy you were before, he seemed like he was headed in the right direction."

I shook my head. "I was a chump," I said. "I was just a kid pretending to be a man."

"And what kind of man are you now?" Eddie asked.

***

I returned to my dishes and as soon as I heard the melodic hum of Mary's voice in the next room, I rushed to greet her.

But in the days that followed, Eddie's words began to burn in me. I'd sit beside Mary at the bar, watching her shovel forkfuls of corned beef into her mouth, and I felt all the ways in which she was making me look like a fool. I started to notice the looks Eddie gave me, the heights to which his eyebrows raised; I became paranoid when other patrons grumbled statements I couldn't hear, convinced that they were mocking me.

I couldn't hack it. I took the rest of the week off. If only I could feel like the ground Mary and I stood on was the same ground, like she didn't exist on some plane I could never hope to reach. Then I could continue to love her. Happily.

That Friday morning -- the day before Valentine's Day, which I was smart enough to know we'd never celebrate -- the alarm on my watch beeped timidly an hour before dawn and I turned and lightly touched Mary's shoulder, whispering her name.

"Lay off, fuckhead," she murmured sleepily.

"Mary, wake up," I said. "I have a surprise for you but we have to take a trip."

She groaned and muttered something in Irish that sounded like it would be hurtful if I understood it.

"Please, Mary," I said. "This is really important to me."

Her eyes opened and focused on me. She ran her tongue through the space between her teeth and exhaled a breath that smelled like vomit. Then her expression came as close as I had ever seen to softening. "This better be good," she said, sitting up.

While she filled her daily flask, I put on a wool cap I'd bought at the Salvation Army on Steinway and buttoned my double-breasted wool coat. I took stock of my reflection in the still-dark living room window, placing my hand inside my coat, Napoleon-style. Mary came and stood beside me in her denim overalls and her yellow raincoat.

"What in Jesus's name are you looking at?" she asked, squinting out into the dark. In the reflection, we looked like we could be siblings.

I led her up the metal stairs to the N train and we sat a yard apart in the nearly empty car -- it was before rush hour and nobody else was riding but a homeless man a bench away, who slept on a layer of newspapers and screamed out in terror twice.

I gazed at Mary, her face scrubbed pink, her mouth resting in a sneer. She picked dirt from under her fingernails with a pocketknife. At Times Square we transferred to the 3, and when the doors opened with a chime at Wall Street, I led Mary up the stairs into the cold morning. We walked east in silence. I periodically wiped my sweating palms on my jeans.

Eventually we began to smell the sweet stink of New York City water, and she eyed me suspiciously. "What's going on in that feeble brain of yours?" she asked, and I thrilled at how lightly she'd said it; I thought I could almost detect a note of affection under her brogue. I said nothing. I led her out onto Pier 11, to an old fishing boat tied to a post, white paint peeling off in strips. Mary regarded the boat coolly and then turned to me.

"I thought we could go fishing," I said.

"I don't sail," she said. "I thought I told you that."

"I thought it might be easier for you," I said gently, "if we went together."

Her eyebrows pinched together above the smashed bridge of her nose. She produced her silver flask from her pocket and took a swig. Then, after a pause, she handed the flask to me. She'd never done that before. I took a sip of what tasted like gasoline and handed it back to her.

"Stop acting the maggot, Christopher Robin," Mary said.

"I don't know what that means," I said.

"Why are you trying to get me in that boat?" she asked.

I cleared my throat. "Mary," I said. "I love you." She promptly erupted into laughter.

"But I think you're keeping things from me," I continued loudly when she showed no sign of stopping. "I want to know why you don't sail. You don't have to keep your past from me. I want you to trust me, Mary. I want to help you."

"I don't sail," she said again. "I get seasick."

I was skeptical. "Why do you own all those fishing poles, then?" I asked.

"They belonged to my dad. I've been trying to hock them for a year now but I haven't gotten a good price."

"Oh," I said. I put my hand on her shoulder. "Did he die on the water?"

Mary looked murderous for a moment, and I anticipated the shrug that would dispatch my hand. But then she dropped her head. "He did," she said quietly. "I saw it. I didn't used to get sick, you know. I used to fish. He taught me how. I was brilliant, damn brilliant. One day, when I was seventeen, Da says, let's take a jaunt on the boat, Mary, and see what we can find. We leave from Schull and we get bollixed. And after an hour a storm wells up around us, and we're too pissed to move quickly. We capsize -- we tip right over. Neither of us is in a life jacket. You can see where this goes, can't you? I cling to the boat, but Da gets pulled away -- up and down under the waves, screaming at me to help him, goddamnit, and I don't. The next morning another fishing boat plucks me up out of the water and we search for him. And we find him. He's shut-eyed, gripping a piece of driftwood like it's a pillow, and he's dead. When they pull the body up, everything from the waist down is missing. A shark got to him before we did."

"My God, Mary," I whispered. "Mary, that's terrible. I'm so sorry."

She began to whimper. I wanted to pull her to me; I wanted that massive ginger head on my shoulder. As I watched her face crumple in grief, I felt a sharp, unmistakable surge of triumph.

I loved Mary for her dazzling strength, the brass spine I knew ran down her freckled back. Now, knowing that there was a difference between my girlfriend and a sea captain, and that the difference was in her soft center, her vulnerable edges -- I felt a satisfaction I could not have anticipated. I'd never loved her more. Her whimpers grew into sobs, and for a moment she emitted nothing but guttural groans from the back of her throat. These gave way to what I thought was quiet moaning, but then I realized that she had begun to giggle. She let out a sudden shout of laughter.

"Oh, you gullible little turd," she cried, throwing her head forward and then back. "My father died of liver failure, last year, because he was a fucking drunk. Jesus Christ." She tipped the contents of her flask merrily down her throat.

My face flushed pink, and without quite thinking, I stepped onto the boat, grabbing the flask from her hand as I left the pier. I had no plan; I only knew that I wanted to be wherever Mary wasn't.

"Give it back," she demanded, still chuckling, her palm open.

I fumbled with the rope that held the boat to the pier. I was trembling, trying to get it done quickly. Mary leaned forward and tried to snatch the flask back, but I held it behind me and pulled at the rope with my free hand.

"Don't be cranky," she snapped. "I was only taking the mickey out of you. Come on now. Give us the flask, at least. Come on, Christopher Robin."

I untied the boat from the pier and I was floating softly away on a quick current.

Mary's skin looked blue in the predawn light. She wasn't laughing anymore. I tossed her the flask, underhanded, because that was the only way I'd ever learned to throw, and because I knew it wouldn't reach her. I watched Mary watch the flask careen towards the pier. She leaned forward with her hands outstretched, but the flask's course was much lower than her reach; I saw her eyes widen as she lost her balance, and then I watched her topple forward. Her body met the East River with a splash. I kept my eyes on the spot where the water had gone white with ripples, waiting for Mary to emerge. A moment later, her drenched head popped up above the surface.

"You bitch!" she screamed. "You bitch! I am going to stab you through the heart! You dickless goddamned piece of shit motherfucker!"

I edged my way around the boat's perimeter so that I could no longer see her. If I closed my eyes and listened to her yells and the sounds the East River made as she slammed her fists down upon it, I could forget pretty easily that she was a real human being whom I knew, with whom I'd shared a bed.

I imagined instead that she was just a man overboard, just a sailor meeting his inevitable end, and that her curses were meant for the sea, not for me. I stepped up to the helm and put my hands upon it, despite having no concept of how to use it.

"Let's have a moment of silence for our fallen comrade," I said out loud, and I stood a little taller, trying to look both sad and noble. After a moment of quiet, I began to sing a song I thought sailors might sing. "Show me the way to go home," I began, but I couldn't remember any of the lyrics and I also realized that I didn't know the tune. The sun was a blurry hint on the horizon and my hands were freezing, but I stood there, pretending to steer my ship, until I could no longer hear my ex-girlfriend cursing at me from the water.

This is Katie Coyle's first publication. It was heavily influenced by the movie Jaws. Katie is currently an MFA student at the University of Pittsburgh. Patrick Coyle is her brother. In all likelihood, he will be far more successful than her.