Punchcard Copyright

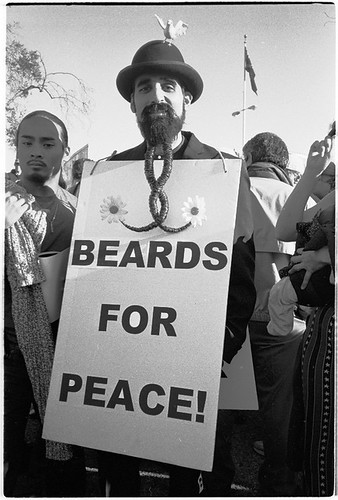

Punchcard CopyrightPeople in Austin understand the amount of dedication it takes to grow a good, gnarly beard, even if the amount of effort involved in other creative commitments is often an alien quantity. As a result of my new facial hair, I suddenly became a local mandarin, and now my voice carried much greater weight than it deserved.

"Badass beard," said my friend Coral with quiet humility. He was trying to dig up a stump in my front yard. I had rented a place in town in an attempt to spread some "East Coast Writer" money around in this troubled community and was paying my acquaintances Coral and Sutphin to do some yard work for me, even though I could have done it myself. After all, I had so much extra testosterone that my face was literally growing hair.

I watched them from my new front porch, sipping a glass of iced tea.

"Thank you," I said. "The hardest part was the itching."

"I know what you mean," said Sutphin, rubbing his own beard. "Once you get past the itching, it is much easier to keep going."

"But still hard though," said Coral, shooting him a look.

"Not as hard as cutting a tree stump out of the ground with nothing but a pair of shovels and foul language," I said generously.

Both Coral and Sutphin looked at the ground and spat, embarrassed. I took a sip of iced tea, clinking the ice in my glass and crossing my legs.

"So tell me gentlemen," I said. "How do you feel about the copyright problem?"

"The copyright problem?" said Coral, trying to feign interest.

"Oh sure," I said. "It's a big deal in THE CITY right now."

"You mean New York City?" said Sutphin.

Coral hit him with his yarnspun beanie.

"Of course he means New York," hissed Coral. And then, more sweetly, to me: "We're not familiar with the copyright problem, Mister Jones."

I stroked my beard as both Coral and Sutphin leaned forward, entranced by my knowing frown. My knowing frown was concealed behind a thick wall of curly brown hair. It was like a framed painting.

"There's two camps," I said. "One group thinks copyright ought to be protected for as long as possible so that creators can have maximum control over their legacy. This group wouldn't mind if copyright lasted forever, and they are always pushing to extend the deadline."

"What's the deadline?" asked Sutphin.

"It's 70 years after the death of the author," I said. "Or 120 years after the creation of work-for-hire intellectual property."

"What's that mean?"

"Like Disney," I said. "It will be 120 years before "The Little Mermaid" will be public domain. Anything made by a corporation is copyrighted for 120 years after it is created. This applies to most movies and video games, for instance."

"I love "The Little Mermaid," said Sutphin.

"So who's this other camp?" asked Coral.

"The motherfuckers," I said. "People who don't want there to be any copyright at all. People who want everything to be free."

"You steal movies and music all the time," said Coral. "I've seen you."

"Yeah, well," I said. "Why don't we take a break and go get some coffee? Ya'll are working too hard."

I stepped down off the porch, rubbing my beard furiously. Coral and Sutphin blinked, dropped their shovels, and rolled up their sleeves. The coffee house was just down the street, but Coral lit the joint that was behind his ear anyway. We smoked as we walked.

"What does copyright even mean?" said Coral. "It's just whether or not somebody can copy your shit?"

"It means all sorts of things," I said. "Not just copying, but distribution, amendment, and performance. Also, copyright applies to making derivative works."

"Like "Little Mermaid" t-shirts," said Sutphin.

"Bingo," I said.

"I wish I had a "Little Mermaid" t-shirt right now," said Sutphin.

"If I had the copyright for that, I'd print one up for you, my friend."

"So how come all these motherfuckers want everything to be free?" asked Coral.

"They've got all sorts of good reasons," I said. "I'm just biased because I make things for a living and this feels like giving birth to children. You want to raise your children the way you want and make sure they parrot your values until you die so that you can influence the future and have some kind of impact on the world. I realize this is stupid, but it is also one of the big reasons people get into the creative arts, even if it isn't one of the big reasons they stay in the creative arts. I want the creative arts to always appear to be a powerful, godlike pursuit of Total Meaning, even if this is total crap. I want bankers to always fear artists."

"I guess people want things to be free so that poor people can experience them," said Coral.

"That's one reason," I said. "Also, they don't like the way corporations inevitably stockpile and dominate creative properties."

We had arrived at the coffee shop. We stood in line, waiting to buy drinks. I looked around. All the cool people had beards. My beard was thicker than most, but not as long as some.

There were a few cool-looking people who didn't have beards, but they looked lost and confused. They were called "girls" I reminded myself.

Coral reached into his wallet and pulled out a stained and beat-up coffee punchcard. It had once been white, but it was now almost brown.

After ten punches, he got a free drink. He only had about four punches left.

"How long have you been holding onto that sad old punchcard?" I asked.

"I don't know," said Coral. "A couple of months."

"All in the hope of scoring one free cup of coffee," I said. "All that time. All that effort. Keeping track of it. Not losing it."

"That's right," said Coral. "It doesn't expire."

"I bet you'd hold onto it for years if you had to," I said. "Decades."

"My whole damn life," said Coral. "I'd pass it down to my kids."

My eyes lit up and I snatched it out of his hand.

"I just had a thought," I said. "What if copyright was like a coffee punchcard? What if every time you made something, you got the rights to do ten different things with it, no more and no less? And you basically got to hold onto it forever, until you -- or your heir -- used your copyright ten different times? What if there was no expiration?"

"I don't get it," said Coral. "Give me back my punchcard."

I waved it in the air.

"Like, say you wrote a novel," I said. "You could publish the novel, and that would be a punch. Every new edition would be a punch. If you made a movie out of that novel, it would be a punch. If you made a t-shirt out of the novel it would be a punch. You would get ten free copyright punches and then your work would go public. You could sell punches on your card, but you could also sell the card ITSELF. But there would be a limit. Not a limit based on duration, but a limit based on uses."

"Huh," said Coral.

I gave him back his punchcard.

We had finally arrived at the front of the line.

"Badass beard," said the barista.

"Thank you," I said.

Posted by miracle on Wed, 03 Mar 2010 13:03:06 -0500 -- permanent link